The Broken Piano: Lessons in Leadership

Do you know the story of the broken piano?

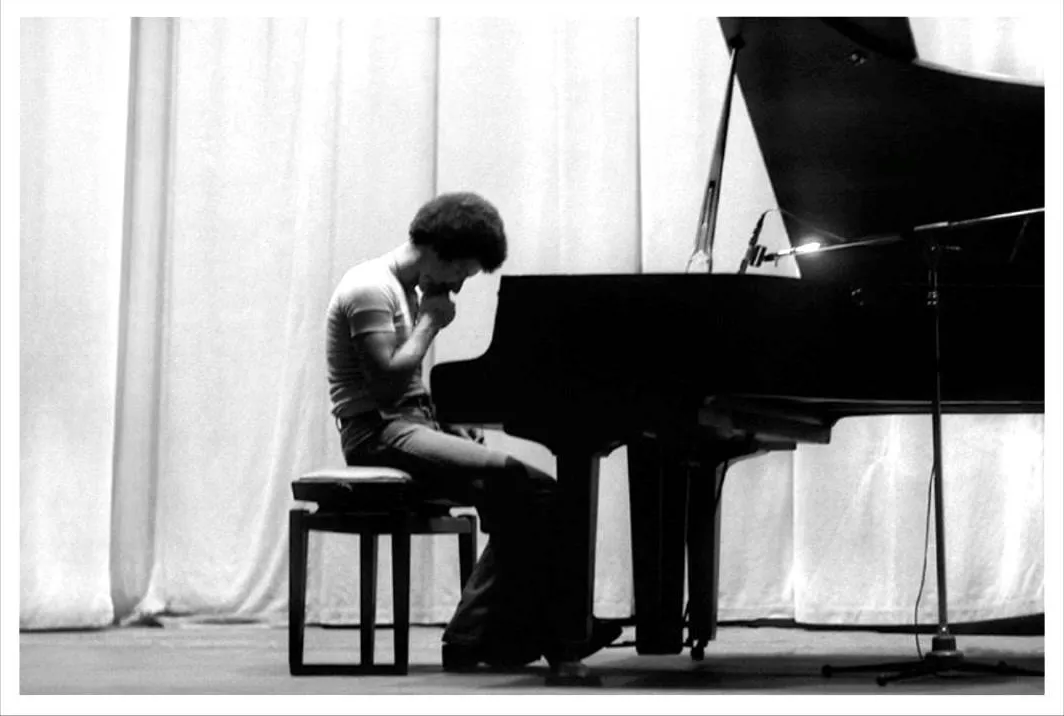

In 1975, legendary jazz pianist Keith Jarrett, 29 at the time, was due to give a solo concert in Cologne. After a long drive in the pouring rain from his last concert in Switzerland, exhausted, with his back in severe pain, he arrives at the concert hall late, tired and hungry only to see that the grand Bösendorfer Imperial piano he had requested was not there.

Instead he is presented with a small, old Bösendorfer that was normally only used for rehearsals. He tries to play it but realizes the piano is completely unsuitable. Some black keys are missing, the pedals keep getting stuck, the bass notes are barely audible.

Now mind you, Jarrett is a musician who demands a lot from his instrument. He plays without sheet notes, improvising live on the stage. He is known for his physicality, his intensity and the high expectations he has on the pianos he plays with.

The Moment of Choice

Given the circumstances he considers dropping out of the concert. The organizers try to rush in a tuner and his son who work feverishly at the piano, but with limited results. And the organizer, Vera Brandes, a 17-year old student, at the thought of having the sold-out concert cancelled, is devastated.

So Jarret decides to spare her and stick to his commitment. He comes on stage at 11:30pm and begins to play on the broken piano.

What transpired was one of the most inspiring live musical moments of all time and the greatest jazz piano album of all time (The Köln Concert), selling 4 million copies and propelling Jarrett into even more international recognition.

He played not against the shortcomings of his piano, but with them. The limitations of the instrument forced him to adapt his style and discover sounds he never even knew existed in him, generating an almost trance-like quality. He created a whole new repertoire forced to exploit the limited range that the piano gave him, and it was glorious.

From Music to Leadership

Here’s how I think it relates to leadership through 8 lessons:

Accept reality early and fully. Leadership effectiveness increases the moment we stop arguing with what is happening and start engaging with it as it is. As Epictetus reminds us, “Do not seek for events to happen as you wish, but wish for them to happen as they do happen.” It’s also one of the fundamental approaches in mindfulness: accepting things as they are and welcoming each moment as if we had created it ourselves.

Work with constraints rather than fighting them. Obstacles often redirect effort toward different, sometimes more grounded paths, revealing capacities and outcomes that would never surface under ideal conditions.

Recognize that obstacles can become openings. What initially appears as a setback may quietly shape a better result, not despite the difficulty, but because of it. As Marcus Aurelius wrote, “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

Adapt without self-pity or blame. Adaptation is not resignation but rather an active, responsible choice to meet circumstances with clarity instead of frustration or entitlement.

Practice self-leadership first. Before leading others, leaders are asked to regulate themselves, their expectations, emotions, and reactions, especially when conditions are disappointing or unfair.

Take full ownership of your response. You may not control the conditions, the timing, or the resources you are given, but you remain accountable for the quality of presence, integrity, and effort you bring to the moment.

Let perseverance be intelligent, not rigid. Grit is not about pushing harder at all costs, but about staying committed while allowing form, method, and expression to evolve.

Stay present with what is possible now. Mindfulness teaches that effectiveness emerges from attention, not resistance, and from responding skillfully to the current moment rather than replaying how it should have been.

Jarrett even said it himself afterwards:

"𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘱𝘱𝘦𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘰 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘐 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘤𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘱𝘭𝘢𝘺 𝘪𝘯 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 -𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦- 𝘢 𝘯𝘦𝘸 𝘸𝘢𝘺. 𝘚𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘐 𝘧𝘦𝘭𝘵 𝘐 𝘩𝘢𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘣𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘳 𝘲𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘥. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘪𝘵. 𝘔𝘺 𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘴𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘴: ‘𝘐 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘥𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴. 𝘐’𝘮 𝘥𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘵. 𝘐 𝘥𝘰𝘯’𝘵 𝘤𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘰 𝘴𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦. 𝘐’𝘮 𝘥𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘵.’ 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘐 𝘥𝘪𝘥.”